1916: an unknown nurses tale

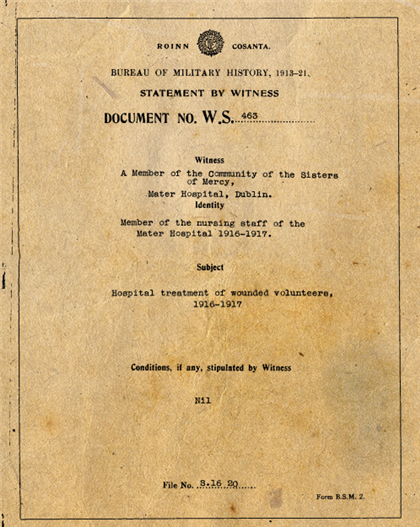

The cover page of the BMH Witness Statement of the unnamed nun who served as a nurse in the Mater Hospital during the Rising.

Stories of 'ordinary' men and women healing the participants of war and dealing with its aftermath are rarely noticed or remembered in history. In this regard, the memory of Easter 1916 is no different to any other war. The staff of the hospitals in Dublin, who dealt with the death and destruction as it unfolded daily, rarely have their stories recalled or commemorated. However, in the depths of the archives of the Bureau of Military History, the intrepid researcher can uncover some of these lesser known tales.

In 1950, the BMH recorded the statement of an unnamed nun, a member of the Community of the Sisters of Mercy, who worked as a nurse in the Mater Hospital from 1916-1917. Her name is unknown, but her words bring the often forgotten consequence of the Rising, the pain and destruction of human life, to the forefront.

The majority of the staff at the Mater Hospital, where our mystery source was based, seem to have been generally sympathetic to the plight of the Volunteers. Dr. Pat McKenna, who, after learning of the car crash which had killed Volunteers in Kerry that Easter Sunday 1916, made sure that the entire hospital staff, especially those working for him knew where his sympathies lay. This sentiment was reflected in how he and the general staff at the Mater Hospital compassionately treated the injured Volunteers who were brought in over the course of Easter week.

The witness details the work of Surgeon Alex Blayney, who never once left the hospital for the duration of Easter week. Operating day and night, he was forced to do so with the most rudimentary tools and in terrible conditions, as gas and electricity lines had been cut. Dr. Blayney relied on the light of the sacristy candles to perform any of his night-time operations, as the patients left their lives in the hands of the ill-equipped team working with unsterilized equipment. The scalpels and stitches they were using could not even be soaked in boiling water as there was nothing to heat it with. Miraculously, during Easter 1916 and the week that followed, none of the patients were reported as having contracted sepsis.

Share the story and join the conversation here!

A British soldier stands guard at the bedside of wounded rebels, 1916.

Tuesday April 25th was the first day that the Mater Hospital received any of the wounded from the Rising. Nine of these were detained and the rest, deemed as civilians, were treated and released. Some of those who died in the caring hands of the hospital staff were Jacob’s factory fore-woman, Margaret Nolan, James Kelly, a school boy who had been shot in the head and John Healy, another schoolboy who had been a member of Na Fianna.

A wounded Volunteer, Patrick McCrea, was brought into the hospital on Wednesday. He had minor pellet wounds in his hand and leg, which he had received while fighting in the GPO. As he was only slightly wounded, he was given a dispatch to deliver out of the GPO, and was ordered to find shelter and treatment afterwards. McCrea was eventually transported to the Mater hidden in a cart of cabbages. However, the ruse failed, as almost immediately upon his arrival, a G Man called McIntyre appeared in the hospital. McCrea was swiftly identified and put under constant watch, with McIntyre refusing to leave even for meals. The student nurses suggested trying to chloroform him, among other things, in an attempt to remove him from McCrea’s door and facilitate the Volunteer's escape.

Eventually, on the 4th of May, the nursing staff were able to supply an escape route for McCrea. While McIntyre had gone downstairs to the pantry to eat, one of the sisters had stolen the key from the Pathological Department to a door which led onto the street. Meanwhile, a nurse named Maire O’Connor brought McCrea along the corridor, through the morgue and to the exit door. Within less than five minutes of leaving his bedside, McCrea had escaped and vanished into the city. The key was quietly replaced by the nun, and McIntyre, who had no evidence of who had aided McCrea or how he had escaped, was left dumbfounded.

Dublin in ruins after the 1916 Easter Rising.

On his escape, McCrea was taken to Carnew in the Wicklow Mountains. He had successfully avoided the police and had arisen no suspicions en route. However, the RIC knew of his name and family details. A recently married man, they had threatened to imprison his wife if he did not give himself up. When the local priest came and told him of this, McCrea felt he had no other choice than to present himself to police. He was transferred to Richmond Barracks and then interned with many of his fellow Volunteers in Wakefield Prison.

On Thursday, Friday and Saturday, the numbers of injured volunteers coming into the hospital increased. As the fighting was reaching its climax, fewer of the injured were surviving, with Thursday being the worst day for deaths, as eight of the nine wounded Volunteers died at the hospital. According to the unnamed nurse, the vast majority of those treated for wartime injury in the Mater were Volunteer soldiers, although most of them had discarded their uniform before being transferred from their military positions to the hospital.

While the unknown witness merely provides a glimpse into the reality of life for those dealing with the wounded during Easter Week 1916, its effect can be sobering. The death toll and suffering, on all sides, that the Rising brought on the city cannot be forgotten as we approach the centenary in 2016.