the "new gaol"

Desmond Stephenson's drawing of the entrance to Kilmainham Gaol

The halls of Kilmainham Gaol are steeped in a long and distinguished history, which dates back to 1796 when the “New Gaol”, as it was then called, was built. The graffiti strewn walls portray a true sense of idealism that defined so many of the prisoners who kept cells in a period spanning three centuries. From the imprisonment of Henry Joy McCracken, of the United Irishmen, in 1796 right up until the release of one of its final prisoners, Éamon De Valera, in 1924, the Gaol is undeniably recognised as an iconic landmark in revolutionary Ireland. Indeed, Kilmainham now offers thousands of visitors each year a chance to experience a place of great social, penal and political relevance to Irish history. But how close did we come to losing it as a historical monument?

After the Gaol saw the removal of its final prisoner in 1924, when the Irish Free State decommissioned it as a prison, the site would never again be used as a place of confinement. Instead, the three-and-a-half decades that followed would see Kilmainham's structure gradually deteriorate through the negligence of a succession of Government bodies. The first of which took control of the prison in the immediate aftermath of its evacuation, when care of the Gaol came into the hands of the General Prison’s Board of Ireland (GPB). It was evident that the GPB had no purpose for the prison as it devoted no time or money into its maintenance. Interest in the preservation of the grounds seemed to steadily dwindle, until an unlikely proposal was brought forth to the Prisons Board. In 1926, Siemens-Schukert, a German engineering company, approached the GPB and requested use of the prison to facilitate their work on the Shannon Hydro-Electric Scheme. The close proximity of the Gaol to Kingsbridge (now Heuston) Station made it the ideal candidate for use as a storage depot for heavy goods, which could be transferred by special rail to Limerick and on to the Shannon River. However, the proposal for this depot required the demolition of the west wing of the prison, which included the old Stonebreakers Yard where the leaders of the 1916 Rising were executed as well as another yard where four republicans were executed during the Civil War. The Prisons Board welcomed the decision to demolish this old part of the building, as it was believed they wished to avoid the inevitable cost of demolishing it themselves. The request was immediately granted, giving an indication that the historic and symbolic significance of the west wing was either not considered or perhaps not truly understood by those in charge. While the building did come to be occupied by several German engineers from early 1927, thankfully no demolition took place on any part of the prison premises. Siemens-Schukert made use of a small number of rooms within the Gaol, with the main hall being used for storage until the completion of the Shannon Scheme in 1929. After which, the German company withdrew their activities from Kilmainham, and the building was yet again vacant and lacking future direction or purpose.

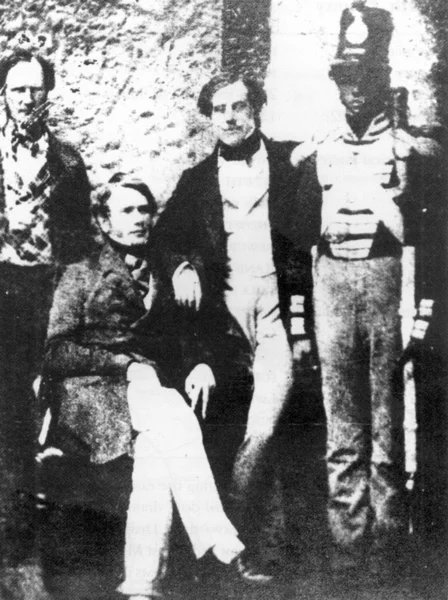

Thomas Francis Meagher, second from right, and William Smith O'Brien, seated, under guard at Kilmainham Gaol after the failed Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848

What's to be done now?

By the 1st of August 1929, a statutory order from Minister of Justice, James Fitzgerald-Kenney, deemed it "desirable for the purposes of economy and efficiency in the administration of the prisons system in Saorstát Eireann to reduce the number of prisons", thus closing the premises and transferring ownership from the Prisons Board to Dublin County Council. Shortly after acquiring Kilmainham, the Council came under increased pressure to decide what would be made of the premises. To the forefront of this debate stood the National Graves Association (NGA) and its honorary secretary, Seán Fitzpatrick. From its inception in 1926, the NGA’s primary objective was to commemorate the men and women who died for Ireland’s freedom. Naturally, it was devoted to securing a permanent commemoration for the 1916 leaders executed at Kilmainham Gaol. Fitzpatrick continually lobbied the Council, urging them to help fulfil his vision of transforming the Gaol from a decrepit structure into a national monument. His personal connection with the prison stemmed from his involvement in the escape of Irish Volunteers Ernie O’Malley, Frank Teeling and Simon Donnelly in 1921. When, using his exceptional knowledge of the surrounding area, he played a significant role in organising and securing their escape. Despite the best efforts of Fitzpatrick, the process of transformation would prove to be long and arduous. It appeared nobody truly wanted to take on the mantle of turning Kilmainham into a historic landmark.

By the late 1930’s, following a request to the Minister of Local Government and former prisoner of Kilmainham, Sean T. O’Kelly, it was agreed that a proposal for redevelopment would be investigated by the Commissioners of Public Works (CPW). This came as a result of the NGA’s and Seán Fitzpatrick’s relentless pursuit of an idea that one day the Gaol would become a site dedicated to the memory of those who fought for Irish independence. Following a number of surveys, set out by the CPW, it deemed the cost of transforming the site into a museum and memorial to the 1916 Easter Rising was roughly £600. Negotiations opened with the Department of Education regarding the transfer of artefacts from the National Museum’s “National Rising Collection” in Kildare Street to the new Gaol museum. Opposition to this was met by both Minister for Education, Tomás Derrig, and Director of the National Museum, Adolf Mahr. Their primary concern was the relocation of precious artefacts to a place they did not deem suitable enough to hold them. It should also be noted that the “Rising Collection” was one of the National Museums most popular attractions and Mahr obviously feared the loss of its prized possession. The concerns expressed by the National Museum and the Department of Education proved sufficient reasoning for the proposal to be temporarily deferred. Despite this, in 1936, it was decided that the state would purchase the premises from Dublin County Council with the intention of preserving and restoring the building and opening it as a museum. In 1937, the Commissioners of Public Works purchased Kilmainham Gaol from the Council for the sum of £100. However, the trend of negligence continued and no further plans were put into action leaving the Gaol to fall further into disrepair. Yet again, efforts were made by Seán Fitzpatrick to place the Government under pressure to revitalise Kilmainham. Following an article of his, published by the Irish Press in March 1938, entitled ‘Shall Kilmainham Fall?’ a special open day was conducted by Fitzpatrick and members of the Seán Heuston Memorial Committee. The event proved a massive success with crowds of people turning up to visit the Gaol. It was hoped that this success would provide incentive for further revival, but the same level of enthusiasm was not shared by the CPW. By 1939, with the outbreak of World War II and the ‘Emergency’, all plans for the Gaol were once again shelved for the foreseeable future.

Throughout the 1940’s, and into the 1950’s, whilst the matter of Kilmainham was discussed occasionally, no substantial attempts were made to redevelop the site. Indeed, by 1953, the Government had finally come to an agreement with the NGA and other lobbyists that it was worthy of preservation as a national monument. However, actions speak louder than words and the situation continued to stagnate. The following year, the newly elected inter-party coalition government made it abundantly clear they did not wish to carry out the schemes proposed by the previous Fianna Fáil government. Hope for the preservation of Kilmainham Gaol appeared to be at an all-time low. If the Government were not willing to invest time or money into a site they owned, what did the future hold for this historic national monument?

Volunteers Unite Once More

Volunteers working to restore the relief above the entrance to Kilmainham Gaol

In order to preserve this iconic landmark, inspiration was needed from somewhere. The Gaol needed a strong character to take the mantle from Seán Fitzpatrick; a man who again and again reiterated the importance of preserving this great monument as a commemoration to all who took part in the struggle for Irish independence. Lorcan Leonard proved to be the man to rise up to this challenge. His interest in Kilmainham rose from the mid-1950’s, when he expressed a desire to create a documentary film highlighting the story of the 'Invincibles', a splinter group of the IRB, of which five men were hung at the Gaol for the infamous Phoenix Park murders in 1882. Leonard, an engineer by trade, sought the help of Seán Dowling, Paddy Joe Stephenson and “Cre” O’Farrell to realise his filmmaking ambition. Planning for the film struck an early, and indeed fatal, obstacle when the Office of Public Work’s (OPW) displayed a reluctance to allow use of the Gaol as a location. The documentary ultimately proved unsuccessful, but Leonard’s vision of the prison’s potential had begun its infancy. Following a notice that the OPW were seeking to demolish the premises, he was provoked into action. His outrage at what he described as “an act of philistines” led him to again contact former Irish Volunteer, and 1916 veteran, Paddy Joe Stephenson. Together they agreed that mass action was crucial in order to stop the demolition. Leonard drafted a proposal centred on voluntary labour that would act to restore Kilmainham to a state suitable for a historical museum. With the support of Stephenson and the Chairman of the Old IRA Literary & Debating Society, Seán Dowling, a meeting was called for at Jury’s Hotel in Dublin in September 1958. This would lead to the forming of the Kilmainham Gaol Restoration Committee.

There was no shortage of enthusiasm to be found at Jury’s the night of the committee’s conception. Amongst the ideas and ambitions for the Gaol, a common understanding transpired that declared “in order to preserve unity of purpose, nothing relating to events after 1921 would be introduced into any activity, publicity, or statements in connection with Kilmainham.” Understandably, dealings relating to the Civil War were still a sensitive issue and could possibly create an unwelcome divide between a voluntary force that would largely consist of ex Irish Volunteers, pro-Treaty and anti-Treaty. Following this agreement, the Restoration Society began to promote the idea to various organisations including the Old IRA, Dublin Corporation and the Irish Congress of Trade Unions. There proved to be an abundance of public support for Leonard’s new plan and all that remained to do was to submit a proposal to the Government. The proposal outlined the complete details for the voluntary restoration scheme, and predicted a timeframe of five years for completion. The structure of the Restoration Society would include a board of trustees who would be assigned the task of collecting artefacts, managing the research programme and compiling a list of the Gaol’s political prisoners. A board of management would be responsible for the scheme’s finances and administering the day-to-day operations on site. On the 21st of February 1960, the Department of Finance finally approved the proposal to restore Kilmainham Gaol. It is believed the proposal brought great relief to the Government who were under mounting pressure to act on the issue of Kilmainham, but were unwilling to provide funding to do so. The fate of the Gaol now lay in the hands of those with the deepest connection to it and those who understood the true potential it held for the nation.

Volunteer Seán Dowling placing the final slate on the restored roof of Kilmainham Gaol's main hall (1964)

The restoration begins

On the 21st of May 1960, the Government officially handed over the keys of the old prison to the Restoration Committee. A five year lease was drawn up, with a nominal fee of one penny per year. At the end of the lease it was agreed that ownership would be transferred to the committee on the condition that a comprehensive restoration had taken place and the premises were suitable for visitor access. Restorative work could finally begin on Kilmainham, with the Irish Press declaring; “From now on such voluntary labour will be found in Kilmainham Jail on Saturday afternoons, on ordinary holidays, during the long daylight hours of summer, carrying out this labour of patriotism until it is completed”. Indeed, a formidable challenge loomed over the project, but the spirit and enthusiasm of the voluntary workers was evident. By October 1960, five months after work began, Seán Dowling announced that over 9,000 hours of voluntary labour had been put into restoring the Gaol. This powerful statistic is a testament to the comradery that existed between the volunteers and without a doubt a similar comradery many of them shared during the 1916 Easter Rising and subsequent War of Independence. The fact that so many of the Kilmainham volunteers had been involved in these pivotal events in Irish history only proved to add meaning and symbolic significance to the restoration effort at the Gaol.

In 1961, the Restoration Committee were given offices at the Carlisle Buildings, in the heart of Dublin City, to be used as an information centre and a place where new volunteers could apply to help with the project. From here they presented an exhibition on the Gaol, which began on St. Patrick’s Day in 1961, before being relocated to the Building Centre on Baggot Street where it remained for two years. The exhibition drew considerable popularity and in turn provided a substantial amount of necessary revenue for the Committee. It was ensured that no stone was left unturned and every opportunity to promote the project and fundraise for it was seized. By the end of 1961, such progress had been made that an ever increasing number of visitors were allowed access by guided tours around the Gaol on Sundays. The year also saw the inauguration of the Restoration Committee as a limited company. It was now recognised as the Kilmainham Gaol Restoration Society.

British Pathé archive newsreel showing President Éamon De Valera visiting Kilmainham Gaol during the restoration of the prison (1962)

The project was advancing more than adequately and the Society was confident the site was in sufficient shape to begin preparation for a historical museum. By now, over 200,000 tons of debris had been removed from the Gaol, yet another statistic that attests to the unity and determination of all involved. In March 1962, a Museum Committee was formed and appointed the task of collecting appropriate material for the historical museum. Although the National Museum expressed concerns over competition for artefacts, similar to those expressed in the 1930’s by Adolf Mahr, the Society’s progress hastened and they began gathering an impressive collection, including an original 1916 Proclamation. Confidence grew in strides for the Gaol and the vision Seán Fitzpatrick had of restoring the decrepit site into a national monument was finally being realised. In 1964, the final piece of major restoration work was complete when the building was fully re-roofed, leaving only a few remaining minor issues to be dealt with before the grand opening.

a new chapter for kilmainham

On Sunday the 10th April 1966, President Éamon de Valera officially opened the Kilmainham Gaol Historical Museum. The opening couldn’t have come at a more suitable time as Ireland prepared to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising. In his address on the opening day, De Valera commended the spirit and patriotism shown by the Kimainham Gaol Restoration Society in the transformation of the site from a crumbling relic, into a historic landmark that Ireland could be proud of. He concluded with:

““I do not know of any finer shrine than this old dungeon fortress in which there has been so much suffering and courage so that Ireland should be a nation not only free, but worthy of its great past. This is, then, a hallowed place and I hope that tens of thousands of our people will come here through the years to visit it and to draw inspiration from it.

It is not to continue bitterness that we want to have this place preserved. The reason that we want it is that it will inspire our people and make them remember the great efforts that were made through the centuries to preserve this nation, and encourage them to exalt it among the nations of the Earth as the men of 1916 wanted it.””

In the years following the 50th anniversary celebrations of the 1916 Rising, the number of volunteers involved in the restoration project began to decline, with several of the original trustee’s, including Lorcan Leonard and Seán Dowling, passing away. In 1986, a decision was made by the Society to transfer the running of the Gaol back to the State under the care of the Office of Public Works (OPW). This proved to be the most practical option for the future of the Gaol and its museum, which gradually benefited from a more structured approach to running the Gaol as a tourist attraction. The opening hours increased and while the guides may not have had any first-hand experience, the service on offer improved. Essentially, the transfer back to State ownership has secured the longevity of the Gaol, just as the men and women of the Restoration Society would have wanted.

The main hall of Kilmainham Gaol as it looks today

Without a doubt, the story of Kilmainham Gaol since 1924 has been turbulent. A considerable amount of credit for the notion of restoration must be given to both Seán Fitzpatrick and Lorcan Leonard. Fitzpatrick’s vision for the Gaol was clearly ahead of its time. Amongst all the indecision and unwillingness to make use of the premises, he remained unyielding in his view that its destiny lay in the form of a national monument that would commemorate the lives of Irish rebels. Likewise, Leonard took Fitzpatrick’s vision to the next stage and was daring enough to propose a voluntary initiative that would transform Kilmainham into the bastion of Irish history that it is today. Without either of these men, who knows what the fate of the Gaol would have been? Both men, visionaries in their own right, just like the men and women of 1798 or 1916, deserve the highest recognition for their efforts to preserve Irish cultural and historical identity. Currently, Kilmainham Gaol stands as one of the country’s largest tourist attractions. In 2008 it attracted a record 299,563 visitors through its halls. The foundations by which the Kilmainham Gaol Restoration Society was founded ring true today, with the old building standing as an educational landmark and a shrine to Irish nationalism, past and present.

- Written by Conor Harte