1916: Paddy Rankin's Story

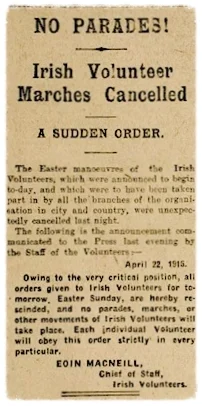

Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order which appeared in the Easter Sunday newspapers in 1916.

In the confusion of the printed countermanding order not to mobilise on Easter Sunday, many of the rank and file Dublin Volunteers stumbled upon the Rising on Monday. For most, their part in the insurrection was the result of unplanned, unexpected circumstances, a chance meeting with their commanding officers in the street or overhearing murmurs of mobilisation on the way to the shops. For those in the more isolated parts of the country, the conflicting reports of official orders which reached them crippled many efforts to mobilise forces.

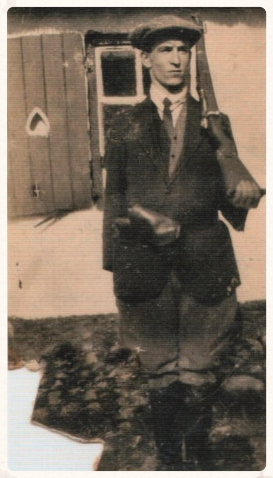

Some, however, were unhappy to await orders to filter through to their rural towns and villages. So they undertook voyages which were so winding and plagued by hazards, that one could write an odyssey on their efforts. Patrick Rankin, of Newry Co. Down, is a man who undertook one such voyage.

In this short documentary, the family of Irish Volunteer Paddy Rankin discuss his involvement in the fight for Irish freedom.

a long journey south

'The only Newry man to take part in the 1916 Easter Rising'

During the week, Southwell and Rankin met the IRB centre in Co. Down, Robert Kelly. A stern man, he declared that he would not accept orders from Co. Louth. This put Rankin in a difficult position and again he cycled to Dundalk on Good Friday night. Southwell had been unable to collect any names of men willing to fight in the uprising. Unsure of their next move, the men were told to inform Kelly that the Rising was official and going to happen the following day. Upon their return to Newry, Kelly stubbornly refused to take Dundalk’s orders, insisting that nothing had come through from the IRB in the North.

Hearing no news on Saturday, Rankin cycled along with his brother Owen to Dundalk. They arrived there in the afternoon, to find that the Dundalk Volunteers had already left and were heading for Dublin! Fearing police interference, the Rankin brothers cycled to Ardee, avoiding the main roads. There they enquired as to whether the Volunteers had passed on their way to Dublin, while they were told yes, Paddy assumed that the locals thought them to be RIC men or spies and they quickly made their way to their aunt’s house in Dromskin where they spent the night.

On Easter Monday they returned to Newry, reporting their findings. By this time the Rising had begun in Dublin, with the Volunteers occupying strategic positions across the city. However, Newry was still out of contact, with no word coming through on the fate of the planned insurrection. Paddy’s friend Peter suggested that himself and the two Rankin brothers cycle to Dublin the following morning to find out what was happening. With few better options, Paddy agrees. However, later that night, while mulling over his decision, he comes to the conclusion that his brother, with a wife and children and his friend Paddy who isn’t even a member of the Volunteers, are better left alive and well at home in Newry. And thus, Paddy takes it upon himself to rise early and be gone before the other two join him at their meeting place.

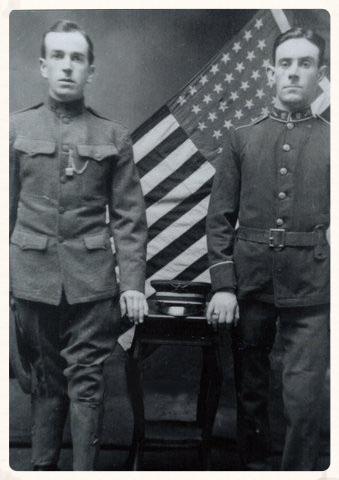

Patrick Rankin (left) in his Philadelphia National Guard's uniform, 1914.

Cycling as far as Cloghue Church, Paddy here swapped his bicycle with that of John Southwell’s, in order to speed up his journey. He continued along the main road until the Jonesboro Church turnoff, where he then went along the back roads of Ardee, to Drogheda and into Balbriggan. As evening was settling in around 7.30 p.m. the heavens opened up and torrential rain drowned poor Paddy as he cycled the final leg to Dublin city. Luckily he made it all the way to his sister’s house in Cabra, just off the North Circular Road, without being stopped by the police. For if he had, the officer may have taken some issues with the six inch revolver up his sleeve.

That night, Paddy went down to the GPO to see how events were panning out. While no police questioned him, his brother-in-law was keeping him under a very watchful eye. Returning for the night to North Circular Road, Paddy hid his revolver and ammunition in the desk drawer of his room. By morning these had mysteriously vanished.

As Paddy surely had realised, his sister and brother were not supportive of his desire to join the Volunteers at the GPO. In order to fight for his cause, Paddy was forced to yet again lie to his family. With his cap in pocket, Paddy declared that he was off outside to clean his bike. In the garden, he took his opportunity and vaulted over the back wall, making his way to Dorset Street. With his Northern accent, Paddy had to be careful as the Royal Irish Rifles, who were patrolling the streets, were a Northern Regiment. Asking a passer-by for directions to the bakery, Paddy successfully skirted around the soldiers of the regiment who were in the area. Armed with loaves of bread (fearing a shortage of food in the GPO) Paddy continued on his way to the Parnell Monument in the hope of gaining some information.

Normality had lost all meaning in Dublin, as the Rising continued into its third day. On Moore Street, Paddy heard shouts of warning. Up ahead was a drunken man, carrying a sword, which he had apparently procured from the Waxworks museum. After picking up the pace and swiftly dodging the drunk, Paddy arrived at the barricades of the GPO, where he was approached by a sentry. Asked for his name and informing them of his hometown, Paddy was placed under the command of Leo Henderson.

Paddy Rankin's funeral courtege makes its way down O'Connell St, Dublin in 1964, passing by the GPO where he served with distinction during the Easter Rising in 1916.

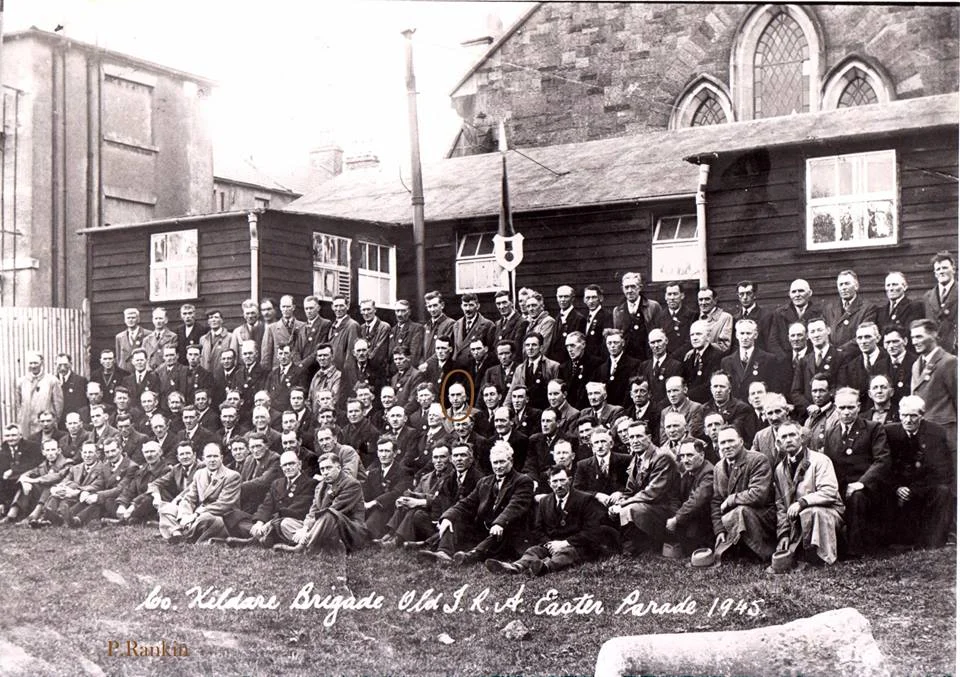

After three long days, Paddy had reached his destination, the GPO. It was here that he would fight alongside his fellow countrymen. Though dismayed at the lack of Northerners who had travelled down for the fight, none of the men had a negative word to say to Paddy about his province. Paddy would go on to be interned at Frongoch, and continued to fight with the IRA in the War of Independence. In his later years, he went on to live and work in the Curragh Camp as a civilian painter. One can think of few men or women who had journeys that were as complicated and arduous as Paddy’s, who despite being three days late and in the company of unsupportive family, still made it his mission to join his fellow Volunteers at the GPO.

- Written by Daire Collins

You can read Paddy's two Bureau of Military History Witness Statements by clicking on the following links: