Tom Clarke, who ordered the creation of the Laois Company of the Irish Volunteers.

In the story of the Easter Rising, the garrisons in the GPO, the Four Courts, and the Citizen Army in the Royal College of Surgeons are all the stuff of legend. The Laois Company of the Irish Volunteers, however, doesn’t spring directly to mind when one thinks of Easter Week. But the men of Laois had an important part to play in the week’s events – they fired the first shot.

The Laois Volunteers were led by Patrick Ramsbottom, from Portlaoise, who had joined Sinn Fein and the Gaelic League in 1906, and having moved to Athlone in 1910, continued his associations with the republican movement there. He joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Athlone and organised a branch of Na Fianna Éireann, the Irish national boy scouts. He was also involved in anti-recruitment campaigns in the lead up to the First World War.

Moving to Dun Laoghaire in Dublin at the outbreak of WWI, he joined B Company, 1st Battalion of the Irish Volunteers, under Commandant Ned Daly. He became friendly with Tom Clarke. The two moved in similar IRB circles. Later that year, he decided to return to his hometown in Portlaoise with Clarke’s blessing to organise a Circle of the IRB there, and to establish a company of Volunteers. On his return to Laois he did just that, and was elected Captain of a company 12 strong.

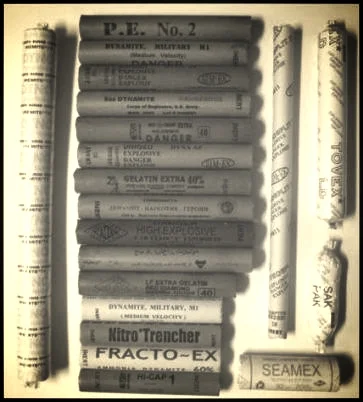

The Laois Volunteers stole vast quantities of Gelignite, which was sent to the headquarters in Dublin.

The Laois Volunteers set about drilling once a week, and were instructed in the use of arms and explosives. One of their notable duties was the procurement of gelignite from the local coalmines, which was transported to Dublin for stockpiling. The company also marched in the O’Donovan Rossa funeral procession in 1915.

April of 1916, the company was informed that an insurrection was imminent, and that they would shortly receive their orders for the uprising. It was impressed upon them at that stage that their orders, when given to them, would remain notwithstanding any countermanding orders that might arise.

As promised, on Holy Thursday the 20th of April 1916, the Laois Volunteers received news that the Rising was set to begin on Easter Sunday at 7pm. Their orders were to demolish the railway line between Waterford and Dublin, disrupting any troop movements between Rosslare Harbour and the capital.

The Volunteers got to work on arrangements for the operation. One of their number, Colm Houlihan, was an employee of the Railway Company and so was able to procure the required tools from the workshop. A section of railway in Colt wood was chosen as a convenient site for cutting the line as there was a curve in the track at this point and it would be more difficult to replace.

Easter Sunday came, and with the impression that the Rising was to begin at 7pm sharp around the country, they commenced operations. They cut down telegraph poles and severed the lines of communication. Using the tools stolen from the Railway Company they removed a number of sections of rail and several sleepers, removing these from the area and dumping them deeper in the woods. As they were carrying out these tasks, a number of passers-by had to be taken prisoner in case they raised alarm.

Monument commemorating the Colt Wood operation.

While the men were engaged in this first act of their rebellion, a heavy rain began to fall. Once finished, they sheltered under the trees in the darkness and waited. Eventually, a light approached. The Railway Company had sent a man out to investigate the cause of the signals failure, a result of the telegraph wires being cut. As he stopped to inspect one of the sabotaged telegraph poles, Patrick Ramsbottom called upon the stranger to halt. He failed to do so, and Ramsbottom fired a warning shot over his head. Hastily the lamp was extinguished and the man escaped into the woods. Soaked to the skin but jubilant in the success of their mission, the Laois Volunteers returned to their safe house.

Just after they left, the railwayman returned in an engine and carriage with five colleagues and four policemen. As the train approached the location of the disturbance, it was derailed and crashed onto its side as it passed over the demolished section of line. The engine driver and fireman were flung from the cab but nobody was hurt.

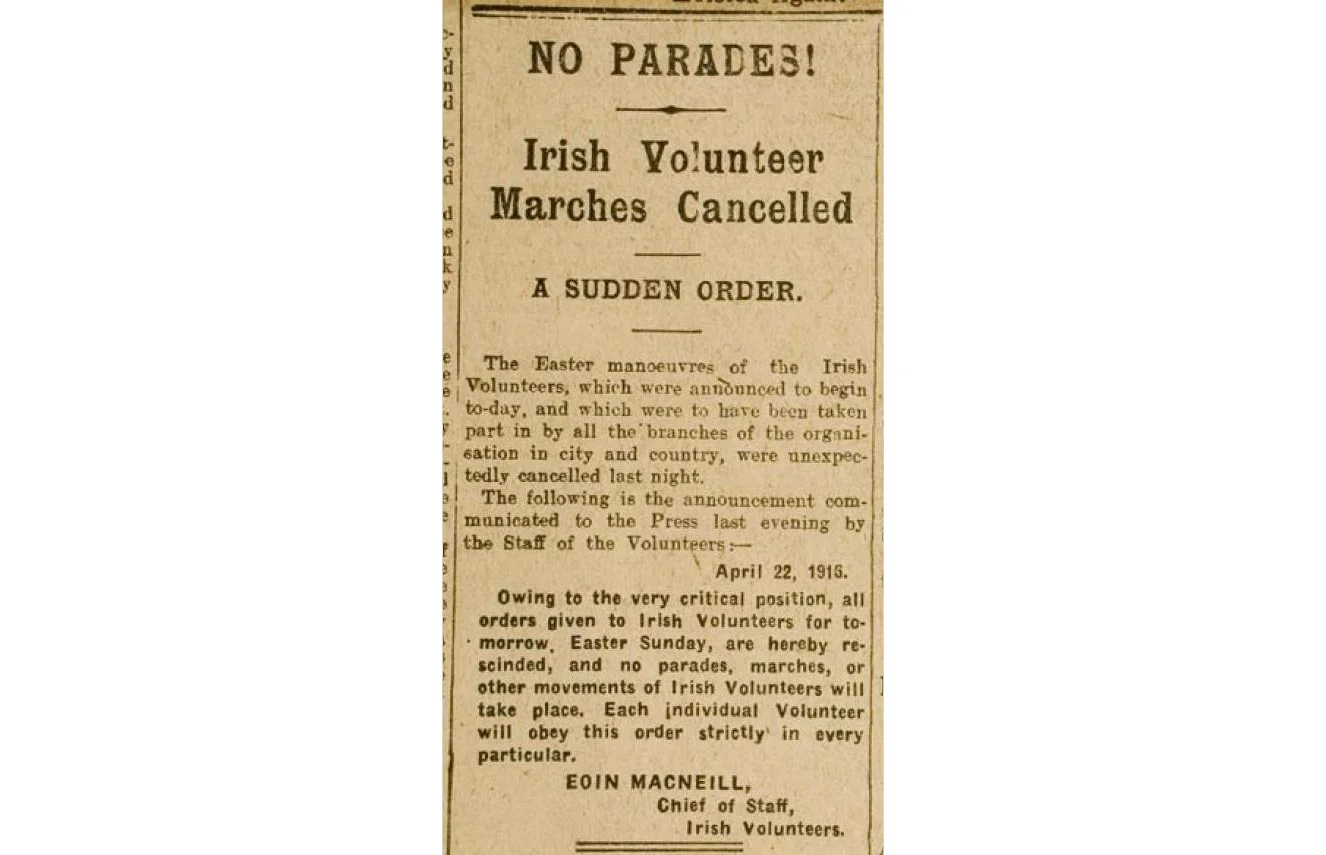

Back at the safe house, the men received the devastating news of Eoin McNeill’s countermanding order, sent after the Aud had been scuttled off the coast of Kerry with a consignment of munitions for the insurrection. They had not, it would seem, been taking part in a countrywide military manoeuvre as they had previously thought. More likely the majority of the Volunteer forces hadn’t turned out, but information was scarce so they resolved to find out the following morning.

Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order, which the Laois Volunteers recieved all too late.

On Monday morning a messenger was sent to Portlaoise and the company learned with regret that the Rising had indeed failed to go ahead. As far as the men could tell, theirs was the only move made against the establishment on Easter Sunday. The situation became clearer to them as they read newspaper reports of the arrest of Roger Casement and the sinking of the Aud. On Monday evening they received the more heartening news that the Rising had eventually gone ahead, and that their operation was not in vain.

A tense period of waiting followed. The men hid out in a farmhouse and awaited further orders. They had been warned not to be misled by anything appearing in the press but rumour and speculation flooded the area about the progress of the Rising. Numerous attempts were made to contact Volunteer groups in neighbouring counties, to no avail. The week passed, shrouded in confusion and conjecture for the Laois Volunteers. No police raids or searches seemed to materialise as a result of the railway job, so the week passed without event.

One of the men, Eamon Fleming, travelled to Dublin to seek more information. He returned with news that the Rising was over, the leaders had surrendered and had been arrested. A day or so later, Fleming again went to Dublin, this time accompanied by Patrick Ramsbottom. Where they met Father Augustine, a capuchin friar close to the Volunteer movement, who told them that the insurrection was over. Returning to Laios, the men decided that since they had not received orders to stand down by their superior officers, they would have to remain active, and go on the run. The company split up and went to different parts of the country. Most went to Dublin, where ironically it was the safest place to hide as the rebellion had been quashed and everyone in the city had surrendered.

The first shot of the Easter Rising failed to trigger the fight anticipated by the Laois Volunteers, although they did succeed in interrupting the railway line. The incident in Colt Wood embodies the false start that arose from MacNeill’s countermanding order. Volunteers across the whole country experienced the Rising in much the same way – tense but in the dark and unsure what to do. They survived the week, but were denied their opportunity to fight for their beliefs.

Ramsbottom and his men reformed their company in 1917. This eventually grew to a battalion, and then a brigade, with him as Commandant. They finally got their chance to fight, as the War of Independence swept across the country the following year.

- Written by Eoin Cody