travelling for the fight

Margaret Skinnider - Doing My Bit for Ireland.

The female participants of the Rising were pioneers in the progression of women’s rights in Ireland. This was particularly true for the women of the ICA, which was a defiant supporter of gender equality for the time. Margaret Skinnider, a Scottish schoolteacher who travelled to Ireland with the sole intention of joining the Rising was also the first participant to publish a book on her role in it. She first travelled to Dublin in 1915, where she was introduced to the world of Irish republicanism and the Irish Citizen Army. In Glasgow, Skinnider had been a member of Cumann na mBan but her sole military training had only come from her time in British run camps set up early during WWI to train a home defence.

When Skinnider arrived in Dublin, like many others without roots in the city, she ended up under the wing of Countess Markievicz. Markievicz’s house on Leinster Road was constantly abuzz with an ever changing guestlist. Used as a shelter by artists and republicans alike, it was said that often, Markievicz would have no idea who was staying until she arrived down for breakfast. Under the guidance of Markievicz, Skinnider was brought into the slums of Dublin, where the old Georgian tenement buildings were still laden with families living on top of each other in appalling conditions. Even one hundred years later, the irony of these desperately poor families living in the former houses of the incredibly wealthy rings as true as it did when Skinnider wrote about it in 1917. .

“I do not believe there is a worse street in the world than Ash Street. It lies in a hollow where sewage runs and refuse falls; it is not paved and is full of holes. One might think it had been under shell-fire. The fallen houses look like corpses, the others like cripples leaning upon crutches.

These houses are symbolic of the downfall of Ireland. They were built by rich Irishmen for their homes. Today they are tenements for the poorest Irish people – the poor among the ruins of grandeur”

On her first trip to Dublin Skinnider was put to the test. She was instructed to go out to Beggar’s Bush barracks, map the area and searching for possible ways to destroy it. Unaware of what the purpose of this mission was, it soon became apparent after she returned with accurate information. After confirmation of Skinnider’s report, she was taken to meet James Connolly. It was from this meeting that Margaret became truly committed to the struggle for Irish independence. She was immediately taken into the fold.

Share the story here and join the conversation!

The spirit of revolution that Margaret had found in Dublin, especially in the ICA had convinced her that she must return for any planned rebellion. Despite protests from her mother, she was set to return to Ireland for Easter 1916. Taking holidays from her job as a schoolteacher in Scotland she did just that. She was put straight to work upon arrival, sent to collect and escort James Connolly’s family from Belfast down to Dublin, and later was tasked with gathering up explosives and ammunition hidden throughout Dublin.

ICA members outside Liberty Hall in 1914

Margaret was one of the hundreds who mobilised at Liberty Hall on the Sunday evening. From that point on, the men and women of the ICA were at war, though they remained largely within their headquarters. Margaret was to be a scout, on Monday morning she was sent about the city on her bicycle to report on the troop movements from the barracks. This was to be Margaret’s role throughout the conflict. While it may sound passive, Margaret was to come under fire more often than many of the ICA and Volunteer recruits, pedalling through the streets of Dublin under hail of bullets delivering vital communiques.

Based in Stephen’s Green originally, Margaret was based in the Royal College of Surgeons along with Commandant Michael Mallin and Countess Markievicz. From here, she ferried messages back and forth to other outposts, originally passing off as a civilian girl out for a cycle. However, as the fighting wore on, Margaret was forced to zig zag down the streets to avoid the incoming sniper fire from the roof of the Shelbourne Hotel. On Tuesday night, Margaret changed into her ICA uniform and took to the roof of the College, and for the first time in her life had fired her rifle at another human. Her training from the British military camps in Scotland and the days spent with the ICA youth paid dividends. More than once Skinnider met her mark, the figures lined up in her sights crumpling to the ground.

“I slipped into this uniform, climbed up astride the rafters, and was assigned a loophole through which to shoot. It was dark there, full of smoke and the din of firing, but it was good to be in action. I could look across the tops of trees and see the British soldiers on the roof of the Shelbourne. I could also hear their shoots hailing against the roof and wall of our fortress, for in truth this building was just that. More than once I saw the man I aimed at fall.”

By Wednesday, the College was under sporadic heavy firing from both machine gun and sniper fire, with bullets cracking through windows, forcing those inside to take cover behind the thick stone walls. Margaret was eager to experience military action and pleaded with Commandant Mallin to allow her bomb the Shelbourne. Eventually he acquiesced to her request and a plan was devised.

Before the Shelbourne could be bombed, Mallin needed to cut off any possible British retreat before attempting to destroy the machine gun outpost. Margaret’s suggestion of firebombing the Shelbourne had stuck with him and he decided that the best course of action would be to the buildings surrounding the Russell Hotel in order to block any retreat from St. Stephen’s Green. Margaret was chosen for the attack party. This was to be her first military sortie of the Rising. Margaret was lucky to escape with her life from their attack on the Russell Hotel. The unit had reached the building unperturbed in just a few moments run. However, once there, a unintended shot alerted the nearby British soldiers to the rebels presence. Soon they were under a hail of fire as the flash of the muzzle had revealed their position. Margaret was shot and was keeling over. Councillor Partridge, one of the ICA men, lifted her up and helped her dash across the road. Here they came across the body of Fred Ryan, a 17 year old who had volunteered for the mission. It took two men to drag Margaret to safety, but she made to the safety of the College.

While her military action was over for the Rising, Margaret refused to be taken to hospital, instead insisting that she be treated in the College by the doctor on duty. Upon inspection it was discovered that she had taken three different bullets along her left side. When she awoke after passing out, she was delirious, suffering not only from the bullet wounds but from the additional ailment of pneumonia. For three days she lay in her cot, surviving on water alone. The college was isolated from the other pockets of rebellion and it was anyone’s guess as to how the Rising was going elsewhere. As the booming of big guns echoed across the city, those holed up inside the College dreamt of German warships attacking the British. These dreams were quickly quashed when artillery began to rain down on them.

The word of surrender came through on the Sunday morning via a despatch rider dressed in white. The young girl was flanked by two British soldiers. On the inside, the order of surrender came as a shock. Margaret was not present for the discussions between the ICA leaders of the college but within an hour she was carted off to St. Vincent’s hospital in an ambulance. Her departure was to be the first move in the surrender at the Royal College of Surgeons.

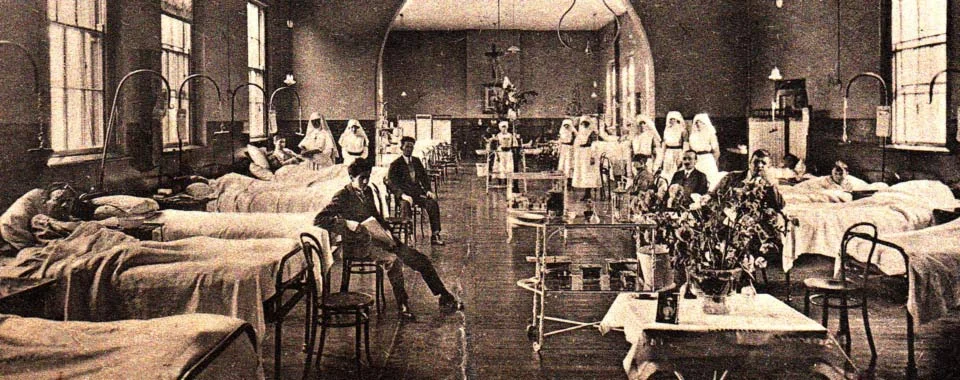

Margaret was badly injured, she was held in isolation for two weeks in a small sterile white room in the depths of Vincent’s hospital. It was only after these two weeks that Margaret that was allowed to write a letter home to her mother, who until then had presumed the worst. After that it was a slow process of filtration that news got through to Margaret as she learned of the fate of the leaders and her friends. The staff at Vincent’s were largely sympathetic and soon Margaret was allowed have visitors. The stories of the aftermath, of both the treatment of the rebels and the hostility of Dubliners shocked and horrified Margaret, who felt trapped and unable to do anything from her hospital bed.

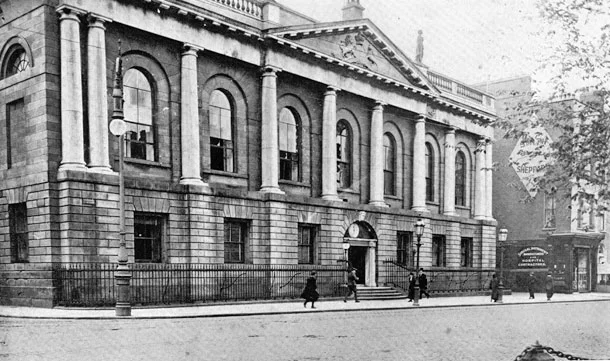

St. Vincent's Hospital Dublin, in the early 20th Century.

Margaret was well known by the Dublin officials. Once she was moved to a public ward, G men started appearing in the waiting area, keen to question and detain Ms. Skinnider. She spent another two weeks there before the detective was allowed to take her away. She was briskly taken to Brideswell prison, where she was placed in a single cell. However, Margaret’s stay in prison was to be no longer than a fleeting visit. Due to a phone call from the Head Doctor of Vincents, Margaret was quickly returned to the hospital by car. When she was finally discharged from hospital the G-man had given up and she left the building a free woman.

Margaret’s journey was not over. She now faced the challenge of leaving the country. Travel abroad was tightly restricted as the military continued to clamp down on civil liberties across the country. In order to travel home to Scotland, Margaret had to obtain a special permit from Dublin Castle. Wanting to return, Margaret took the huge risk of walking into the belly of the beast. She threw off her sling and attempted to look as normal and civilian as possible as she entered the gates of the Castle grounds. Where it had once made her stand out from the crowd, her ‘loyal’ Scottish accent was now a huge benefit for her, putting the guards at ease. After dissuading any suspicions of the first officer, she was walked to the office of the military authorities for Dublin. Again there were no hard questions and Margaret Skinnider, the Scottish ICA rebel was allowed walk out a free woman.

Margaret did not stay long at home, by August she was back in Dublin. Her writings recall how much had changed across the city. Republican colours were everywhere and there was little doubt in the mind of the public that the executions were the cause of this change. Quickly Margaret realised that she was being followed by government agents. Tensions were high, and as a former rebel Margaret no longer felt safe in the city, within weeks she was on her way to America.

Lower Manhattan in 1917, the year of Skinnider's visit.

Her work for Irish independence continued in the US, as she toured the North of the country attempting to raise funds and awareness for the struggle for Irish independence. She travelled with Kathleen Boland for some time and was heavily involved with the Cumann na mBan there. She was the first of the participants to write and publish a book on the Easter Rising. Even this book, ‘Doing My Bit for Ireland’, was intended to raise funds for the republican cause. In 1917, after her lecture tour and some promotional appearances for her book, Skinnider decided to return to Ireland.

She continued her role in Cumann na mBan and when Civil War broke out she took the Anti-treaty side, becoming the Paymaster General of the Irish Republican Army. In December 1922, Margaret was again arrested, and this time would serve out a longer sentence than before.

In 1925, merely three years after the end of the Civil War, Margaret, who had returned to teaching, applied for a Wound Pension from the Army Pensions department. This was an unusual move on Margaret’s part, given that these were the very people she had been at war with three years earlier. However, from the pension records files, the officials issue with allowing this pension lie more with the fact that Margaret was a woman, rather than an anti-treaty supporter. Despite her lasting injury, Margaret would not get approval from the Pension board until after De Valera got into power, in 1938. She continued to live in Ireland for the rest of her left, working as a teacher until retirement in 1961.

- Written by Daire Collins