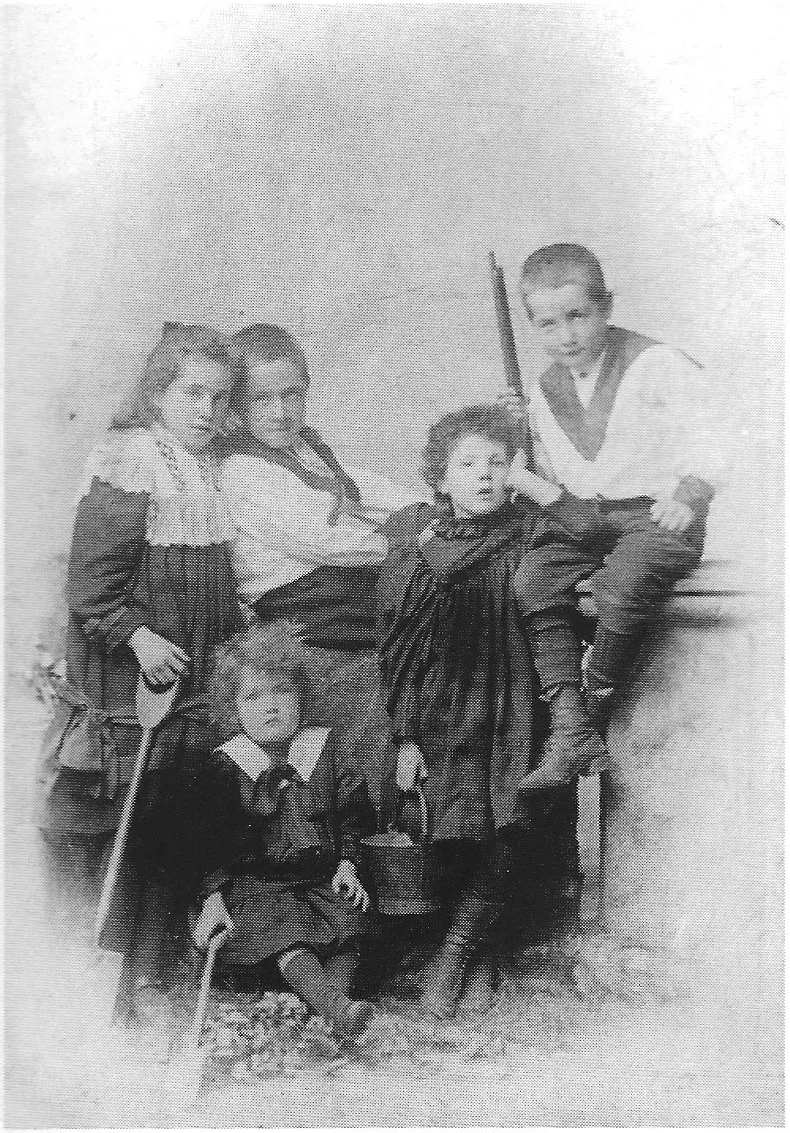

Kathleen Boland (left) with her siblings, including Harry (right)

The Bolands had revolution in their blood, and these rebellious genes were just as apparent in Kathleen Boland as they were in her three brothers, Edmund, Gearóid and Harry. Their grandfather lived in Manchester and was involved in the legendary raid on a prison van, resulting in the escape of two Fenian leaders. Their father Jim Boland, a child at the time, was also used as a scout on that occasion. He grew up and returned to Ireland to start a family, and became a close friend of Parnell’s. He died from a brain abscess after receiving a blow to the back of the head at a nationalist meeting that ended in a confrontation with Anti-Parnellites.

When he died in 1985, his family were at risk of becoming destitute. However due to Jim’s close ties to several leading figures in the nationalist movement, including the GAA, IRB and nationalist members of Parliament, a fund was raised to purchase a tobacconist business for the Boland family. This helped maintain the link between the family and the nationalist movement as the country moved towards a crucial period at the start of the 20th Century.

The three Boland brothers all became members of the IRB, and the Irish Volunteers at its inception. They also became members of the GAA, and it was Harry Boland, having met Michel Collins at a GAA meeting, who encouraged him to join the IRB.

Kathleen Boland was uniquely positioned, therefore, to witness the events of Ireland’s Nationalist struggle in the early 1900s. By 1914, the family home was in Marino Crescent in Clontarf, and Kathleen invited some Volunteers she was familiar with to store the rifles from the Howth Gun Running in the back garden of the house. She was there on Easter Monday morning when her three brothers went out to partake in the Easter Rising. When Harry broke the news to his mother, Kate, she replied “Go, in the name of god – your father would haunt you if you did not do the right thing!”

Kathleen Boland (back left) with Ena Shouldice, and (front row, l-r) Harry Boland, an unknown friend and Jack Shouldice

On Monday afternoon Kathleen, eager to lend a hand, went down to Gilbey’s wine depot in nearby Fairview, which had been taken over by a band of Volunteers including Harry. She brought them food, and delivered several consignments of ammunition to them, including some she knew Ena Shouldice had hidden in her house. In the aftermath of the Rising, she received word that her two older brothers, Harry and Gearóid had been arrested. They were imprisoned in England, Harry’s death sentence having been reduced to five years penal servitude.

One day in 1917, a letter arrived in the house, accompanied by a note which read “My daughter found this paper in the streets of Lewes and, as I too have sons doing their bit, I forward this letter, as the writer desires, to his mother.” It was from Harry. The letter began “I hope some kind angel will pick up this letter and send it to my mother, Mrs Boland, 15 The Crescent, Clontarf, and earn the prayers of her son” and went on to gave a detailed account of the ill treatment of the prisoners in Lewes Jail. Due to the strict censorship rules in Lewes Prison, the sending of such a letter involved a great deal of effort and luck. Harry was being transferred from Lewes and had somehow managed to attain a pen, and wrote the letter on both sides of a piece of prison toilet paper. The warders searched him, but he fought vigorously against them and they did not manage to find the piece of paper, which he had hidden on his person. During the journey he flung the letter out the window of the prison van where a sympathetic stranger luckily found it.

Kathleen brought the letter immediately to Michael Collins, who called a meeting to protest against the treatment of the prisoners. In the ensuing demonstration, a policeman was killed with a stone and Count Plunkett and Cathal Brugha were both arrested. A week later the prisoners were released. Kathleen and Harry hosted a large party of the freed men at their house in The Crescent that night.

Share the story here and join the conversation!

After this, Kathleen settled into regular Cumann na mBan activities, preparing emergency rations for Volunteers on the run, leaning first aid and how to shoot. Harry and the other Boland men were regularly wanted by the police as known republicans, and the house was often raided. They kept a small stepladder on the top landing of the house so Volunteers could escape through a skylight and across the roofs of The Crescent. On one such occasion, two detectives called to the front door, and Kathleen called out the window to them that there were only women in the house and the raiders would have to give them time to get dressed. Harry, Jack Shouldice and two other Volunteers duly escaped over the roofs, while Kathleen slowly showed the detectives around, starting with the back garden, outbuildings and kitchen in order to give the men time to escape. When they reached the upstairs landing, one policeman noticed paint and splinters on the ground below the skylight, and voiced his suspicions. However, when Kathleen asked him if he would like to go up to check, he merely shook his head, presumably afraid he would be shot as soon as he opened the hatch.

Harry Boland, Michael Collins and Eamon de Valera

During this time, as well as the Boland house being used as a safe house, Harry’s tailoring business on Middle Abbey Street was used as a dispatch centre and arms store for IRA use. It was here that the men involved in the Soloheadbeg Ambush, the first engagement of the War of Independence, were brought. Kathleen was charged with finding safe houses for them to hide out in, and took two of them herself to The Crescent.

While the vast majority of participants in the Rising had been freed by this time under a general amnesty, Eamon de Valera remained in Lincoln Jail as the leader of Sinn Fein. Michael Collins and Harry went to Manchester to attempt to free de Valera, staying with a member of the Boland family who lived there. They brought with them a key Gearóid Boland had made based on a drawing sent in a Christmas card. They also sent over two blank keys and a file in a Christmas cake. Gearóid’s key broke in the lock but they had better luck with the blank key, which had been filed down to fit the lock. De Valera was out, and they quickly dressed him in a fur coat and disappeared into the night, blending in with the furtive nighthawks who frequented the dark streets surrounding the prison. Once they returned home, Kathleen was given the key to keep safe until such a time as it could be placed in the national museum.

Harry then travelled to the United States as the de facto Irish ambassador, to raise funds and awareness for the first Dáil. In his absence, Kathleen looked after the tailoring shop on Abbey Street, which was still a key IRA call office and store for large quantities of guns, ammunition and explosives. At one point, when the Abbey Street was surrounded by Black and Tans, Kathleen and a shop assistant made several trips to another IRA premises on Parnell Street with large parcels of gelignite. Harry, in America, had arranged for a large consignment of the then new Thompson submachine gun – the Tommy gun – to be smuggled into Ireland. They were demonstrated to Michael Collins in the shop. A hidden recess behind the fitting room held about 50 rifles for use by the active service unit of the IRA, which Kathleen handed out, as they were needed. She also carried messaged in Croke Park for Michael Collins on Bloody Sunday, and although searched, managed to safely deliver them.

Number 15 The Crescent, Marino. Unlikely home to the Russian Crown Jewels from 1922 to 1938

When Harry returned from America, he brought with him an unexpected cargo. While the Irish contingent was travelling the country, they met a Russian group, who were also raising money for their fledgling republic, although they were having less luck at the time. The Irish lent the Russians a sum of $20,000, and the collateral for this loan was a number of the Russian Crown Jewels. On his return to Ireland, Harry met Michael Collins to give him the jewels. They had a serious row however over the terms of the treaty, and this was the end of their friendship. Collins threw the jewels back to Harry, saying “Take these back, they’re blood-stained.”

Harry returned to the house in The Cresccent, showing signs of having been in a physical struggle with Collins, and gave the jewels to Kathleen and instructed her to keep them safe until Ireland had regained its sovereignty, as per the terms of the loan. They kept the jewels in the house, hiding them in various places including in the chimney recess behind the stove in the kitchen, and in a hidden compartment in the hot press. During raids by Free State soldiers, Kathleen’s mother would carry them around on her person. Only in 1938, when de Valera was once again in power and had passed the constitution, did Kathleen deem Harry’s request to be fulfilled. She gave them do de Valera, who duly returned them to the Russian state.

On the 2nd of August 1922, Harry was staying in the Grand Hotel in Skerries. In the middle of the night, the hotel was raided by Free State soldiers, who went straight to Harry’s room. After a struggle, Harry was fatally wounded by a gunshot. Kathleen visited him in hospital that night. She knew straight away that he was dying. However, she said, “You’ll get over this, Harry!” “Ah no, Kit! I don’t think so,” he replied. She asked him who fired the shot. "I'll never tell you, Kit", he said. "The only thing I'll say is that it was a friend of my own that was in prison with me that fired the shot. I'll never tell the name and don't try to find out. I forgive him and I want no reprisals.”

Kathleen followed in her brother’s footsteps, and went to America along with Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington to fundraise for the Prisoner’s Dependents Fund. After over a year there and in Canada she returned.

The statement Kathleen Boland gave to the Bureau of Military History ends with the line “I got married then.” She had made her contribution to the Independence struggle, and settled into married life in a house on the Clontarf Road.

-Written by Eoin Cody