1916: A Rebel Librarian

A young Paddy Joe Stephenson

Before The Rising

When you think of a librarian, you probably don’t think of a daring young man, a member of the Irish Volunteers, Quartermaster for ‘D’ Company, 1st Battalion, who stole, smuggled and stored arms around Dublin City, a man who stormed a building with just 12 of his comrades and held it for three days under intense fire, like Paddy Joe Stephenson. But a librarian he was, and as it turned out, it provided a great cover for him at times.

Paddy Joe grew up on Upper Tyrone Street, now Railway Street, in Dublin’s then-infamous ‘Monto’ red light district, the biggest in Europe at the time. Its size was accounted for by the volume of British troops training and posted in Dublin, and the residents would perhaps have had an unfavourable view of the behaviour of the soldiers in their community. This may also have contributed to the fact that the area was a hive of Irish Volunteer and IRA activity at the start of the 20th Century.

Stephenson attended the O’Connell School, which produced many notable Irish Nationalist figures including Eamonn Ceannt, Sean T. O’Kelly, Frank Flood and Sean Heuston. After leaving school, he became a trainee librarian with the intention of sitting the Dublin Corporation clerkship exams. Although Paddy Joe had been a member of the Gaelic League and the Fianna Boy Scouts from an early age, he did not join the Irish Volunteers at their inception in 1913, as he was engaged in his studies and working the late shift at Thomas Street Library. Having missed out on participating in the Howth Gun-running in 1914, the sight of his friends parading in uniform finally persuaded him to join the Volunteers.

Paddy Joe joined D Company, 1st Battalion of the Irish Volunteers, which was based in Colmcille Hall on Blackhall Street in Stoneybatter. The Captain of the company was Sean Heuston, who he remembered as an older student in the O’Connell School. Joining the Volunteers gave him for the first time, “a sense of belonging to something worthwhile”. He quickly busied himself with republican activities and proved himself a trustworthy and useful soldier to his superiors.

Share the story here and join the conversation!

Jimmy Stephenson discusses his grandfather's republican activities in the lead up to The Rising.

On one occasion, he accompanied Michael Staines, Quartermaster of the Dublin Brigade of the Volunteers, on a trip to transfer a consignment of rifles, in a pony and trap, from Blackhall Place to Inchicore. Staines decided that the best way to complete this journey would be to take a shortcut straight through the ‘Old Man’s House', the Royal Hospital in Kilmainham. In addition to being a functioning hospital and home for aged and unwell British soldiers, the building housed the Commander-in-chief of the British Army in Ireland. Startled at the decision, the driver of the trap exclaimed “for god’s sake Michael, are you out of your mind, we’ll be pinched guns and all. Don’t you know this place is lousy with tommies?”. Staines replied; “There is not a chance in a million they will suspect us. They will never dream that we would drive through here if we were carrying guns. Go on, smile, and drive past those soldiers as if you were going to Strawberry Beds at Lucan”. Amazingly, the men passed through the army checkpoints without arousing any suspicion. Staines, who went on to become the first Garda Commissioner, remarked; “the more openly you do it, the less you’ll be suspected.”

On another hair-raising occasion, Sean Heuston armed Paddy Joe with a revolver and asked him to accompany him to Kingsbridge Station (now Heuston Station). Heuston was wearing a long trench coat that reached down to the ground. Once at the station, the pair watched a party of British soldiers disembark a train and file into the canteen, throwing their kit bags on the platform and leaning their rifles against the station wall. Heuston marched down the platform and stealthily snatched a rifle from against the wall and hid it under his coat. The pair successfully made it out of the station and returned to Colmcille Hall.

These instances clearly proved Paddy Joe’s mettle under difficult situations to the Volunteer leadership, and Heuston made him Quartermaster for the company. As the Rising approached and the search for weapons intensified, a tip-off was given about a young soldier who, having returned home to Dublin on leave from the trenches, intended to desert and wished to dispense of his uniform and gun. Paddy Joe along with his close friend and fellow company member Sean McLoughlin set out to the house specified, finding a young man of about eighteen huddled by a fire, wearing a uniform still covered in mud from the trenches. They gave the boy's mother two pounds and left with a Lee Enfield rifle and full soldier’s kit including a sniper’s sling full of ammunition.

Paddy Joe’s efforts as Quartermaster ensured that D Company were a very well armed force, prepared for a large-scale engagement with the British Army. Planning for this rebellion was well underway, although the secretive nature of the IRB ensured they didn’t know about the precise plans until the day they happened.

Easter Week

The confusion surrounding the mobilisation planned for Easter Sunday and its last minute cancellation left the rank and file Irish Volunteers in the dark as to what the eventual plan was. Orders were given to stand by and no one was to leave the city. That night, Paddy Joe attended the regular Sunday night Ceilí at Columcille Hall and noted “the dancing that night had a dash about it that was not usual. The rebel songs too were sung with greater defiance and the choruses made the roof ring”

Stephenson was one of a number of Volunteers who kept guard in the hall overnight and in the morning they were sent out as dispatch couriers. It was clear at this stage that something significant was underway, although the men were not entirely sure what was planned due to the secretive nature of the rebel leaders up to that point. One of the men boiled up some eggs for breakfast, which left Paddy Joe feeling violently ill after the meal. However, he was not about to let his sickness get in the way of him playing his part in what was to be a momentous occasion in Irish history.

Irish Citizen Army on parade outside Liberty Hall

He set out for Liberty Hall to deliver a message to Commandant Thomas McDonagh, and on arrival, met James Connolly standing on the steps, watching the sun rising across the Liffey. Stephenson later recalled; “He seemed without a care in the world, and I would not like to have to swear that he was not humming a tune under his breath.” Having dispatched the message to McDonagh, he was given another communication to deliver to Liam Tannam in Wilton Terrace by the Grand Canal on the southside of the city. The message made clear that something serious was about to take place. Paddy Joe then disobeyed orders to return to Liberty Hall with a receipt from Tannam, preferring to return to his own company in Blackhall Street, anxious to fight alongside his comrades.

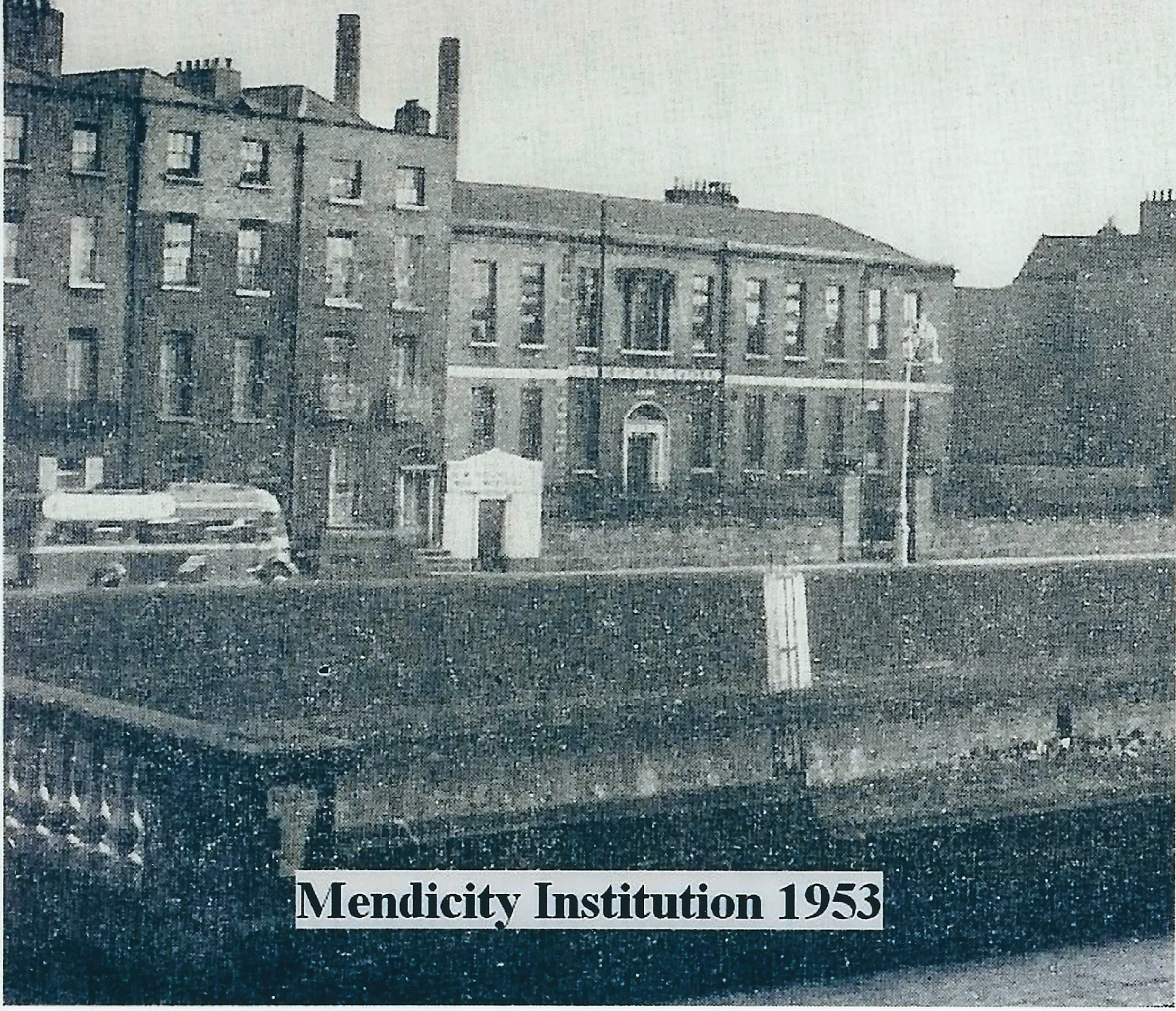

D Company marched along the river from Beresford Place, the men still unclear as to what exactly was happening. Concerns that it had been called off again grew as they marched further down the Liffey. However, these concerns dissipated when they drew level with the Mendicity Institute on the Quays adjacent to the Four Courts. Captain Sean Heuston turned to face the men and shouted “Company left wheel, seize this building, and hold it in the name of the Irish Republic.”

The Volunteers rushed inside the building and set about fortifying it against the inevitable British attack. Furniture was upended and used to barricade the windows and glass was smashed out of their frames. Curtains were torn down and ornaments were smashed and piled up in the fireplace, to prevent against injuries from flying shards in gunfire.

A passing policeman stopped to investigate the disturbance and shouted in to Volunteers that they were “going too far with this playing soldiers”. One of the men shouted back: “Don’t you know the Republic has been declared and your bloody day is done!”. This remark was underlined when the Volunteer fired his revolver in the air, causing the policeman to flee down the quays, losing his helmet in the process.

The Mendicity garrison now settled down into a state of nervous anticipation as they awaited their fate. The men knew that the Irish Republic would be declared at midday on the steps of the GPO, and their instructions were to hold the Mendicity and prevent troops coming from the Royal Barracks (now Collins Barracks) from marching along the quays towards the Four Courts and into the city centre. They knew that this engagement would come, and it was just a matter of waiting.

Finally, the Volunteers spotted a long column of Royal Dublin Fusiliers marching out of the Barracks onto the north quays. The orders were to wait for Heuston’s signal, a whistle, before firing. The strain became too much for one man however, who fired a shot before the main body of troops had reached the intended position, which was to be when the Regiment had drawn level with the building. This first shot, that broke the silence on the quays and signalled the beginning of the violence for the Mendicity garrison, was followed immediately by a volley of others. All the men at the windows let go in a thundering barrage upon the troops across the river. Paddy Joe emptied his magazine in an un-aimed and automatic burst of firing. After this first fusillade the men steadied themselves into more careful and methodical firing, each shot aimed and with a purpose. The troops across the river took shelter behind the river wall and in a passing tram, which stopped and had been abandoned. Stephenson spotted one British soldier crawling along on the ground below the tram. The description he gave of his first experience of the grim realities of combat highlights how powerful an incident it was.

Jimmy Stephenson discusses his grandfather's involvement in the Easter Rising.

“The crawling stopped simultaneously with the sound of the shot. Whole he was being dragged back at the top of the tram the boots under the platform offered a too inviting target and by the time the eyes focused again on the gap at the top another victim was waiting and got it. Then the space under the front platform presented its sandy coloured target and you let go. For a long while this kind of grim triangular target practice went on without a single shot being fired back from the tram as it stood there mute and immobile”.

The soldiers regrouped, and later from the bottom of Queen Street they began to attack the Mendicity with a machine gun. The front of the building was raked with bullets for an extended period of time, and all the Volunteers could do was take cover. Stephenson and Sean Heuston, anticipating a charge on the building, went to another room and prepared some of the homemade paint tin bombs they had brought. Paddy Joe reflected that if the bomb failed to go off, he could at least knock a soldier unconscious by dropping it on his head. The machine gun fire stopped, and the charge never came, for the time being at least.

This episode made clear to the men of D Company that their position in the Mendicity was a precarious one, as the building was open to attack from a number of vantage points. It was surrounded on all sides by a 6-foot stone wall, behind which soldiers could approach with enough cover to throw over grenades. Also, it was detached from neighbouring buildings and set back from the road by about 40 feet, so it would have been relatively easy to knock holes in their sides in order to have a commanding position to fire upon the building. The Volunteers had already experienced how vulnerable they were to attack from the opposite side of the Liffey.

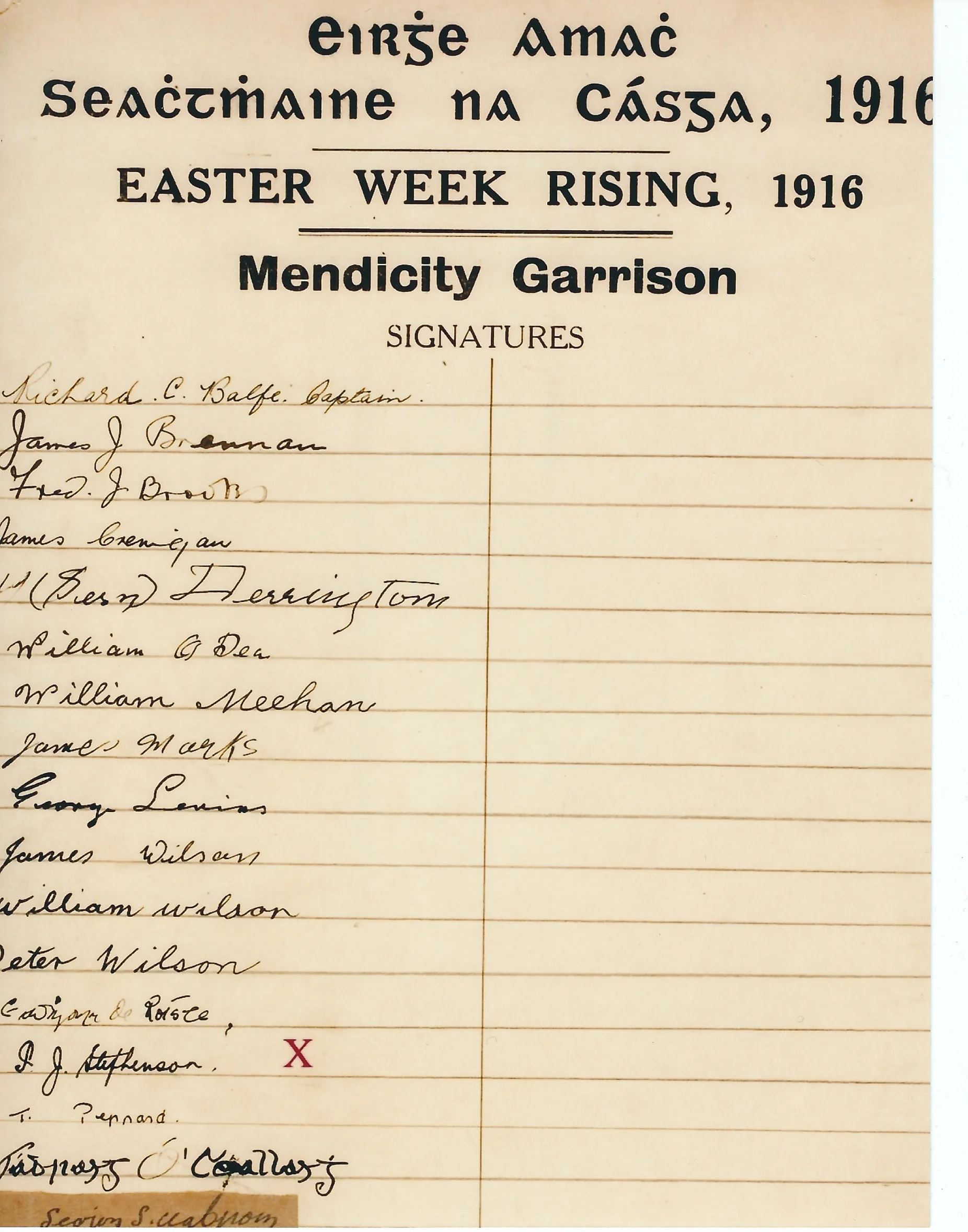

Signatures of the Mendicity garrison. Paddy Joe's is marked with an X.

With this information very much on their minds, a shout came from downstairs that the British were attacking their position, coming over the rear wall. As the men rushed down to defend the building, they realised it was Seán McLoughlin returning from the GPO with reinforcements. As they climbed through neighbouring gardens, they discovered a British soldier hiding in one. They took him prisoner and sent him over the back wall of the Mendicity first, causing alarm to those inside.

On Wednesday, Paddy Joe, in his role as Quartermaster, informed Heuston that there was no food to feed the garrison; particularly now that reinforcements had arrived. The 7-pound bag of rice he found in the kitchen at the start of the week hadn’t held up long, so Heuston sent him and McLoughlin, who had already completed a number of trips across the city, out on a mission to the GPO for food. The pair were fired upon by British troops as they ran, and later they had abuse shouted at them by some local women standing in a doorway on the corner of Bridge Street and Usher's Quay. Eventually they made it across to the GPO, which they entered through a row of shops on Henry Street, and over a roof into the rear of the building.

Laden with food, they embarked on the dangerous cross-town trip once more. When they reached the river, they were disheartened to look across to the Mendicity to see a British sentry at the front door. The building had been taken while they were gone. Crestfallen, they joined the Four Courts garrison, consoling themselves with the fact that their perilous mission had in fact saved them from capture, and that they were still free to “have a whack at them for Heuston and the garrison of the Mendicity”.

Paddy Joe’s memoir ends here, although he continued to fight at the Four Courts and then in the GPO for the rest of the week, before finally surrendering with the rest of the Irish Volunteers on Saturday. After the Rising, he was interned in Frongoch, before eventually being released as part of the general amnesty in September 1916.

Close Brothers, With Differences

While all of this was going on however, a much more curious story was unfolding, one that would have a far greater impact on Paddy Joe and his family.

Paddy Joe’s father, Patrick Stephenson Senior was employed as head stableman in Farrell’s Undertakers, on Marlboro Street. A firm ‘King and Country’ man, he would have been proud of his son Edward, who joined the army and went off to fight in the trenches in France. However, Paddy Joe’s membership of the Irish Volunteers would have been a point of contention between the two brothers, and with his father too.

Jimmy Stephenson discusses the incredible story of two brothers on either side of the conflict

During the Rising, Patrick Snr. decided to go to the stables on Marlboro Street to tend to the horses, as they hadn’t been fed since the start of the week amidst the confusion and fighting. While at the undertakers, he performed his duties in the stables before gathering up what food he could find for himself and his family. However, as he left the stables, unaware that a curfew had been called during the time he was out, a soldier spotted him. Mistaking him for a looter, he shot him on sight. He was one of the hundreds of unfortunate civilian casualties that week.

Patrick’s lifeless body lay on Marlboro street for the rest of Easter week. In a bizarre coincidence, his son Paddy Joe and Sean McLoughlin intended to pass down the street on their trip to the GPO in search of supplies. However, a British barricade blocked their way and they decided to take another route. Paddy Joe would not find out about his father’s death until he was interned in Frongoch a number of weeks later.

Meanwhile, Edward received word that his father had been killed in a rebellion in Ireland and wrongly assumed that his brother had carried out the shooting. Returning home on compassionate leave, Edward intended to find Paddy Joe and kill him. However, when he arrived in Dublin, he realised that his brother wasn’t the culprit, and was in fact a prisoner of the British Army due to his role in the Rising. Further to this, he realised that his father had been slain by a soldier of the same army that he had risked his life fighting with in the 'Great War'. Returning to his home, he walked out into the back garden and burned his uniform. He never returned to serve again with the British Army and had to leave the city as he was a wanted deserter.

Edward and Paddy Joe never harboured ill feelings towards one another after this incident and remained on good terms, although they would rarely see each other except for at family funerals or similar events. The incident could indeed have saved Edwards life due to him not going back to the horror of the trenches in Europe.

Mary ‘Mamie’ Kilmartin

A figure central to Paddy Joe’s life from an early stage was his future wife Mary ‘Mamie’ Kilmartin. Mamie’s mother, 'Granny Kane', was an ardent nationalist and a well known figure in the Stoneybatter area where she was the proprietor of Kanes fruit and vegetable shop. In the period leading up to the Easter Rising, Paddy Joe was able to use Kane’s to store arms and supplies in his role as Quartermaster for ‘D’ Company, 1st Battalion.

Jimmy Stephenson discusses his grandmother's role in the Stephenson family.

Mamie was an active member of Cumann na mBan around this time, while her brother Patrick Kilmartin joined the Irish Volunteers. Her republican activities in the lead up to the Rising included the preparation of first aid kits and food rations. During Easter Week, she was a member of the first aid detachment tending to the wounded in the Four Courts garrison.

On the 17th of September 1917, just over a year after Paddy Joe's release from Frongoch Internment Camp, Mamie and he were married at the Church of the Holy Family on Aughrim Street. Paddy Joe’s best man was his close friend Sean McLoughlin, with whom he had shared many perilous experiences during Easter Week 1916. After her marriage, Mamie ceased her republican activities with Cumann na mBan, as she put her responsibilities as a wife, and soon thereafter, a mother above all else. She did nonetheless fully support Paddy Joe in his War of Independence endeavours and continued to hold strong nationalist feelings.

The Central Bank of Ireland on Dublin's Dame Street, designed by Paddy Joe and Mamie's son Sam Stephenson.

Sean and Paddy Joe went on to become founding members of the Irish Communist Party, having been ideologically motivated by the socialist movement of the time. Mamie however, as a dedicated Catholic, did not agree with the principles of the party and gave Paddy Joe an ultimatum – to choose her or the Communist Party. He subsequently retired from the party and settled down to his work in the Dublin City library service.

Paddy Joe and Mamie were married for 43 years and had five sons, all of whom became extremely successful men in their own right. Their youngest, Sam Stephenson, became one of Ireland’s best known architects, using the Modernist and Brutalist styles to create some of Dublin’s most iconic buildings, including the Central Bank and Wood Quay offices.

- Written by Eoin Cody